My Allerton Artist-in-Residence Diaries Week 2

Week 2: Transitive Landscapes

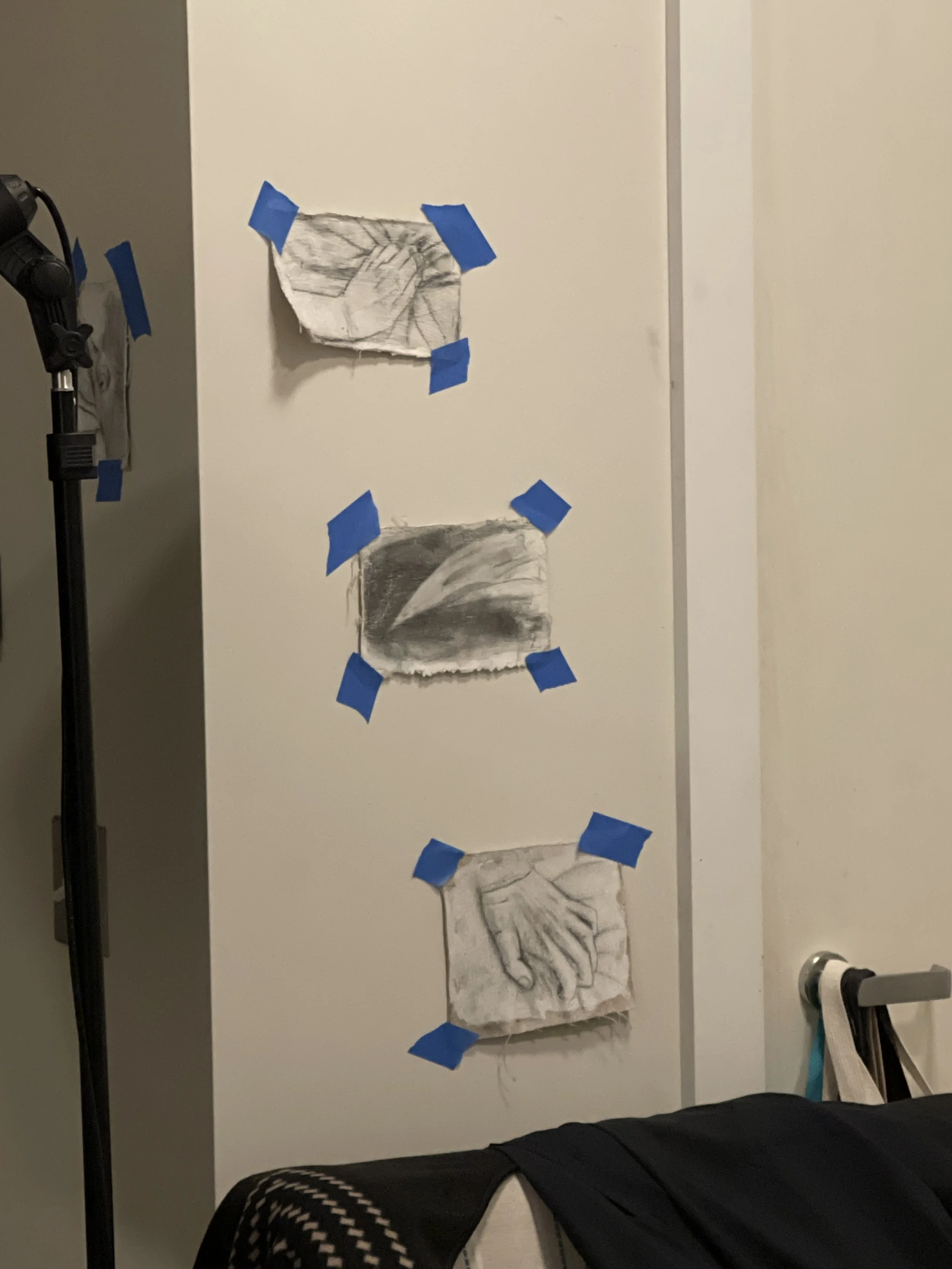

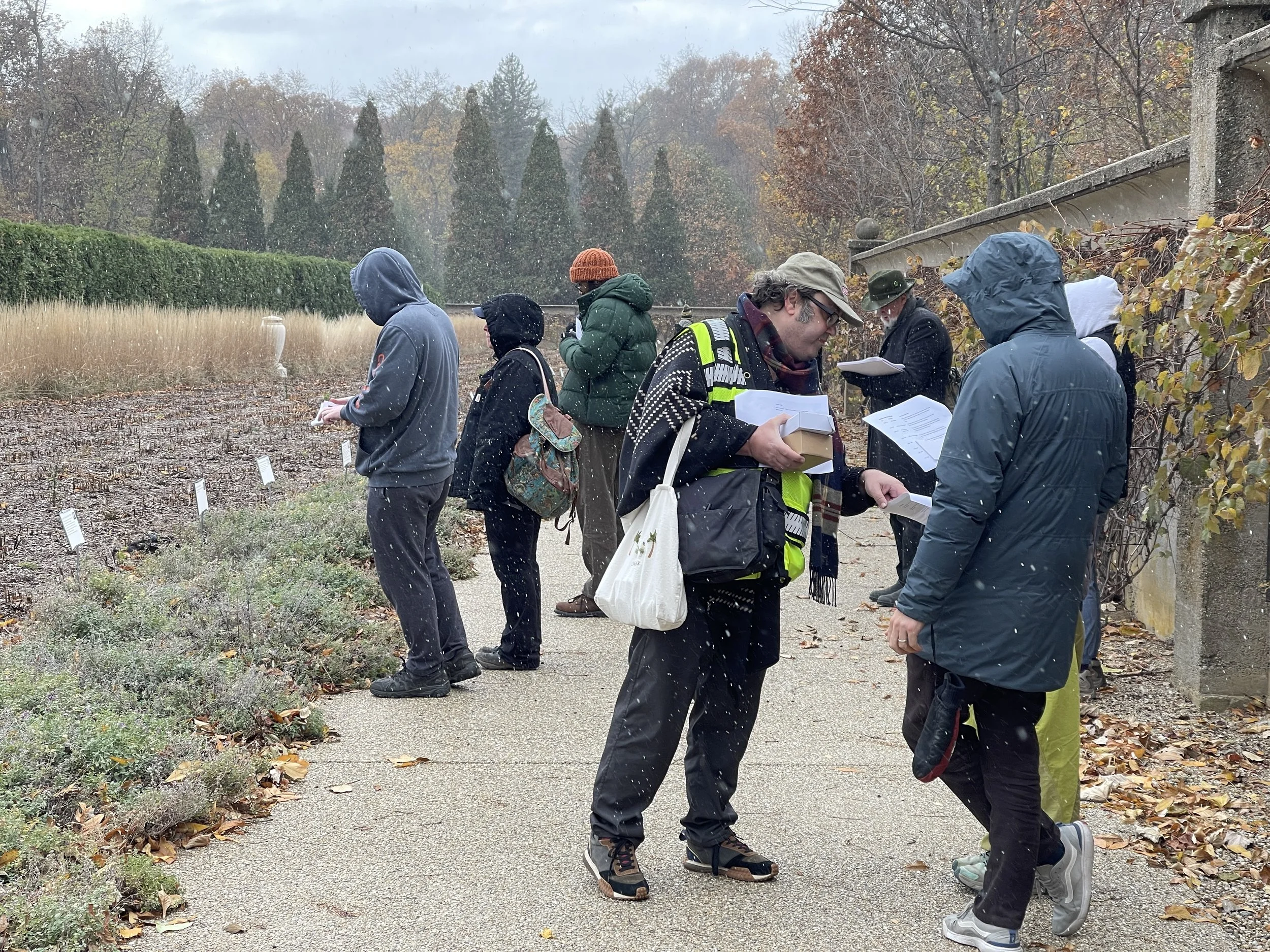

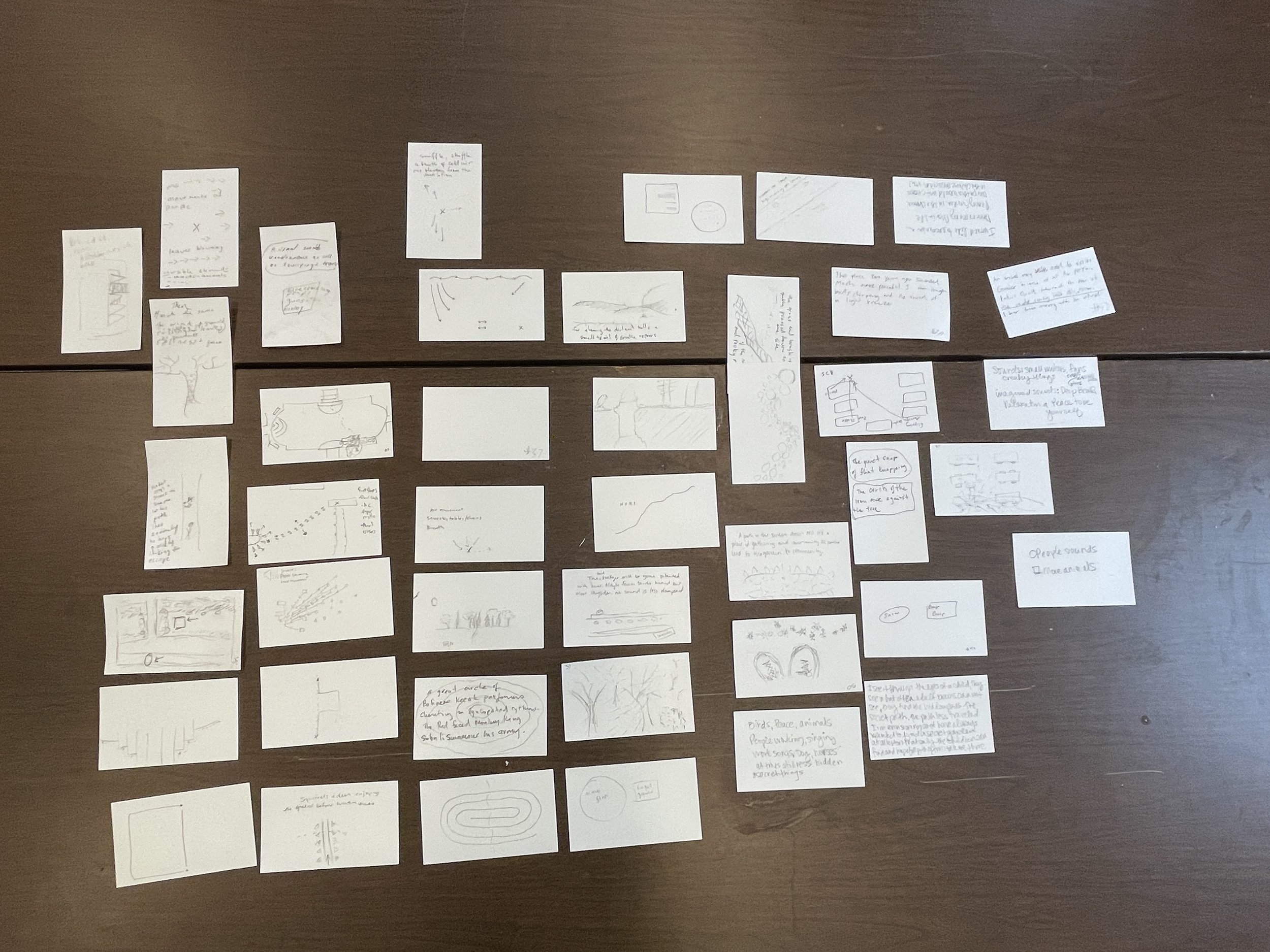

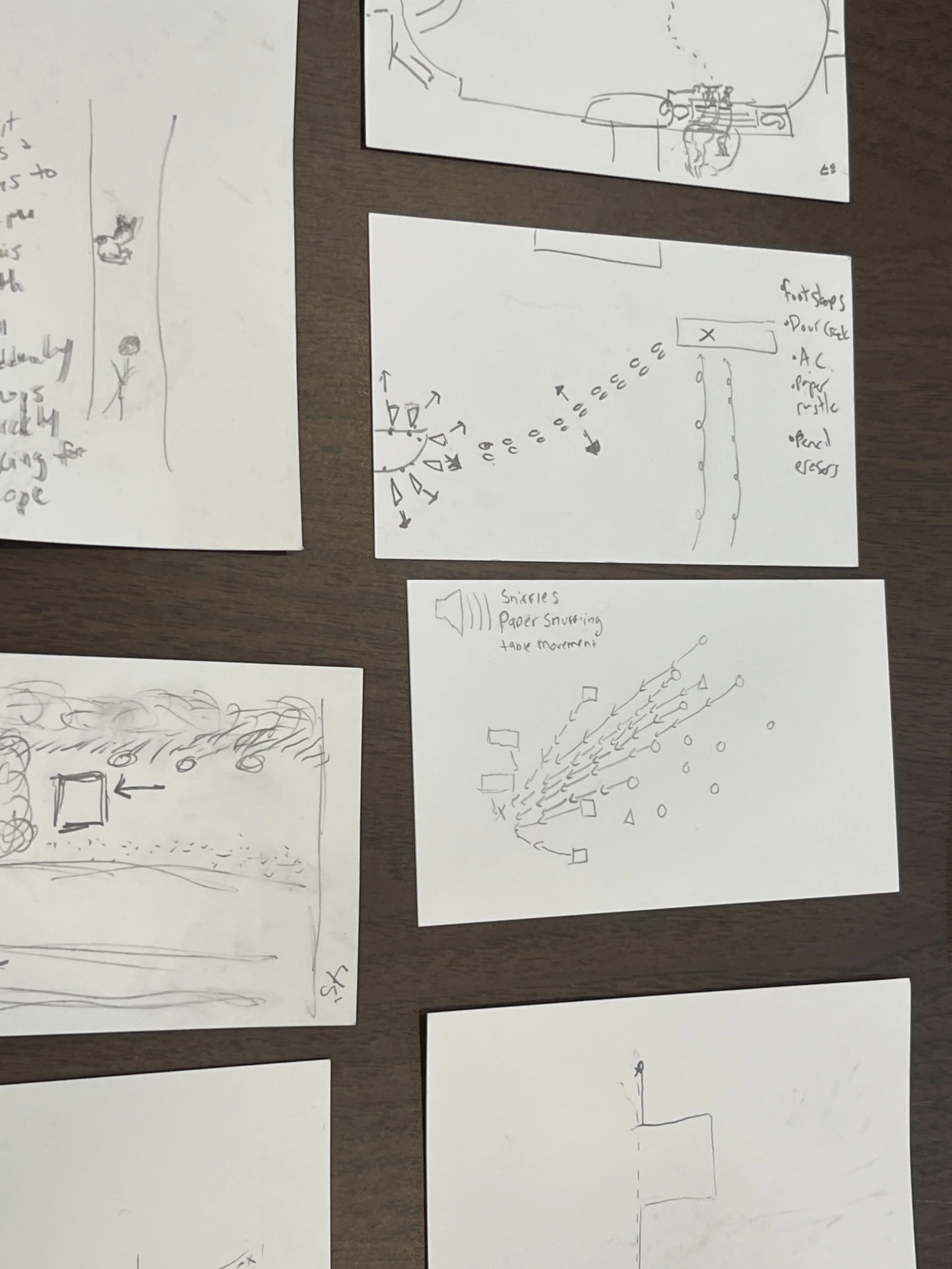

It’s been such a busy time here that it’s difficult to know where to begin this week’s diary entry. It’s really been more than a week since I last wrote, of course, and in that time, the first few warm days—when it was still possible to ride my bike around comfortably—have given way to the coldest cold stretch of the year so far. Winter snow now begins to fall, and I’ve had to stow the bike away in the hallway by the A-frame entrance. Somehow that simple act, of sliding it in against the wall, makes the season’s turn feel more final. Those early warmer days were a gift. I’d ride through the grounds, along the edge of the gardens and out past the park’s periphery, where everything begins to blur into forests and field. It’s a good way to get oriented—to feel the slope of the place, how it moves from the sculpted and ornamental into the rough and unkempt. When the cold finally came, it also meant I could turn inward, unpack the last of my supplies, and start to lay out the studio in a more deliberate way. I get all my materials out of their bags and begin tacking up the precursor drawings—the studies for future oil paintings. Lining them up together, I start thinking about their lineage, how the marks shift over time, how each one opens into a slightly different vocabulary of gesture. That process of re-seeing, of noticing changes across the drawings, helps me acclimate. It’s the way I get comfortable in a space: by surrounding myself with traces of where I’ve been.

Then, inevitably, my body intervenes. My persistent hypertension comes back hard, and I fall into a few days of near total exhaustion. My heart racing between 150 and 190 beats per minute—high enough that most doctors would tell you to call an ambulance. I don’t. Instead, I rest for long stretches, letting the hours pass in that strange haze where you can’t tell if it’s morning or evening. So much of those first few days are spent just watching the numbers on the monitor rise and fall, the pulse climbing and dropping as if it were a kind of weather system inside me.

Still, I manage to get some painting plastic down on the floor, to claim a small area for oil work. Even through the fog of fatigue, I find myself looking at that empty expanse of plastic like a promise, a thing waiting to happen.

When I finally feel strong enough, I manage to conduct an initial tour of the gardens, the entrance to which is directly across from the residence and studio buildings. Here's a short video:

My energy returns. I settle in and start painting, beginning with color and shape studies—big, gloppy gestures that are really about the brush itself, about the materiality of the paint and the act of shaping thought in the white space, the empty page. Getting back into oil has been one of the central goals of this residency. So much of the past few years has been taken up by performance work and other writing, by the Active Investigations and Ghost Army series, that painting had fallen to the side.

So that means I’m still in the midst of the Hundred Canvas Project which I began three years ago now, most of which are drawings, and this felt like the moment to return to the medium that I built so much of this phase of my artistic practice on in the first place. I wanted to see what would happen if I worked directly from the environment here—no precursor drawing, no compositional plan—just color, weight, touch, and the sense of place.

In earlier years, most of my oil paintings were figurative. I wanted, during this residency, to turn that impulse outward, toward landscape. But not landscape in the classical sense—more like a study of orientation, a testing of perception. It’s about asking what happens when I paint from a position of immersion rather than observation.

Here are a few samples of about half of the initial work-in-progress color study beginnings I began working on; I've been weaving in and out of them, switching from one to the other back and forth as I go, and planning a last one on panel for the final stretch.

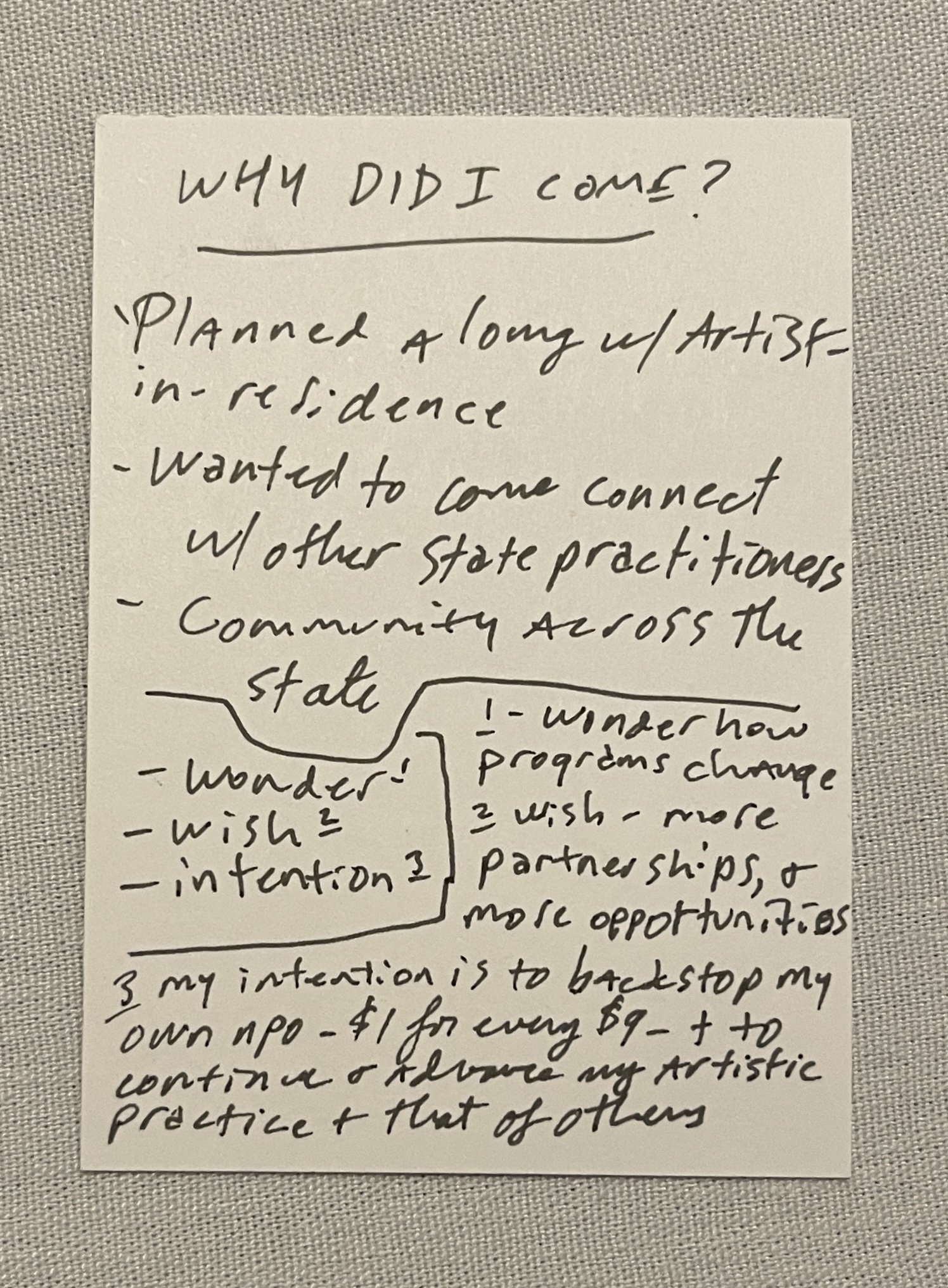

Just as the painting rhythm begins to come into view, it’s suddenly time to leave for Champaign, to the Airbnb I’d booked for the Illinois Arts Council’s One State Together in the Arts conference. The change of environment is abrupt: from quiet field and dark wood to the flicker of electric flame in a rented room.

In fact, the Airbnb has this little electric fireplace mounted into the cabinet under the TV. None of the streaming channels work—no subscriptions, just the bland glow of login screens—and the remote barely functions. So instead of fighting with it, I’d turn on the heater and watch the fake flames move while I wrote or caught up on emails. The hum and warmth of it filled the room, and it was oddly comforting, like a stand-in for the real fire I don’t have in the studio.

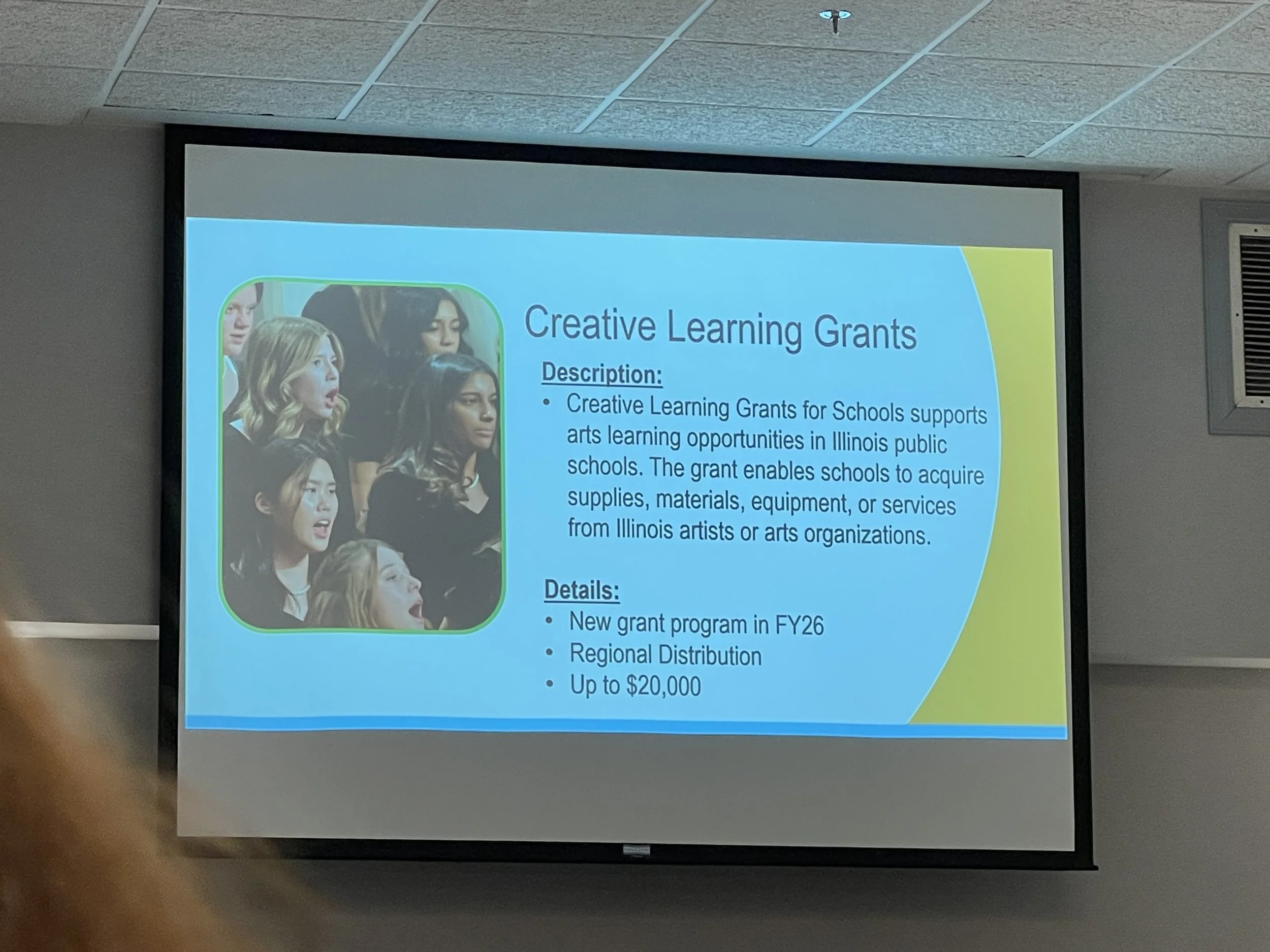

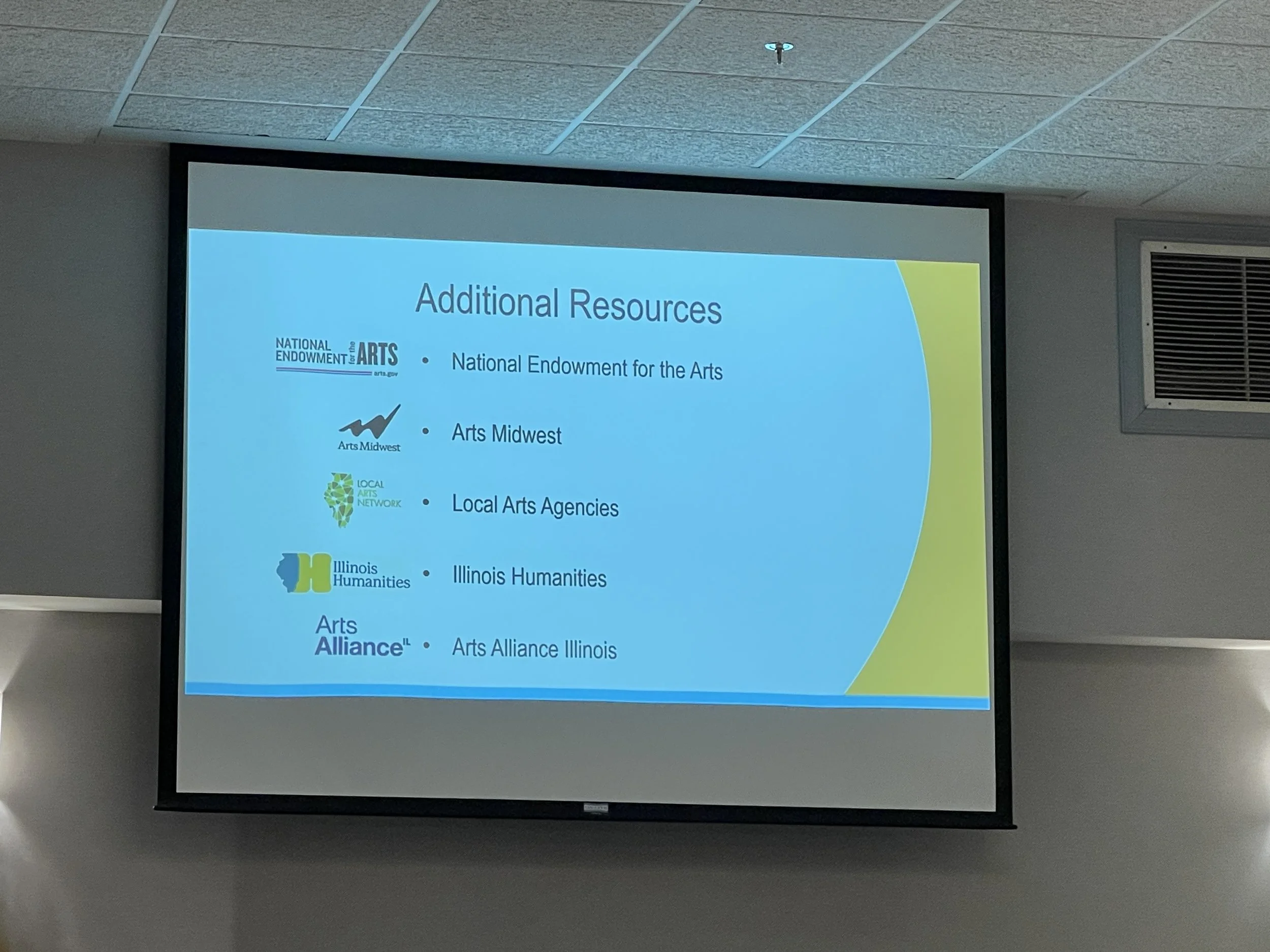

The conference itself is packed and pleasantly bustling: Wednesday is a warehouse-sized assembly dinner and panel, followed by a Thursday full day of talks by the leadership of the Illinois Arts Council and Illinois Humanities, outlining their commitments to the state’s cultural mission, and labyrinths of breakout sessions designed to connect arts and humanities organizations with each other across a buffet of shared interests. It’s always good to meet people working on parallel paths—to hear how small institutions manage, survive, collaborate. Dozens of conversations ensue over meals, meetings, hallway encounters. I try to get in as much conversation as possible, collecting ideas, names, possibilities for partnership.

After the conference, I stay in Champaign through the weekend, and my son Tristan—now a junior at the University of Illinois—comes by, then also a few friends. We spend Saturday afternoon walking the grounds, and eventually get a tour of the mansion. They’re delighted by it; I'm delighted they're here. One of the main motivations for applying to the residency beyond my own artistic practice was my son Tristan's recent move from Wright college in Chicago to the two years in his engineering pathway program down here to the University of Illinois (which also owns and stewards the Allerton Park & Retreat Center where the Joan and Peter Hood Residency is hosted). There’s something endless about the 137 acres in general, but also specifically about the structure of the mansion—the mix of grandeur and secrecy, of public facing programs and public art and hidden corridors—that connects directly to what I’ve been exploring here in performance research and oil paint.

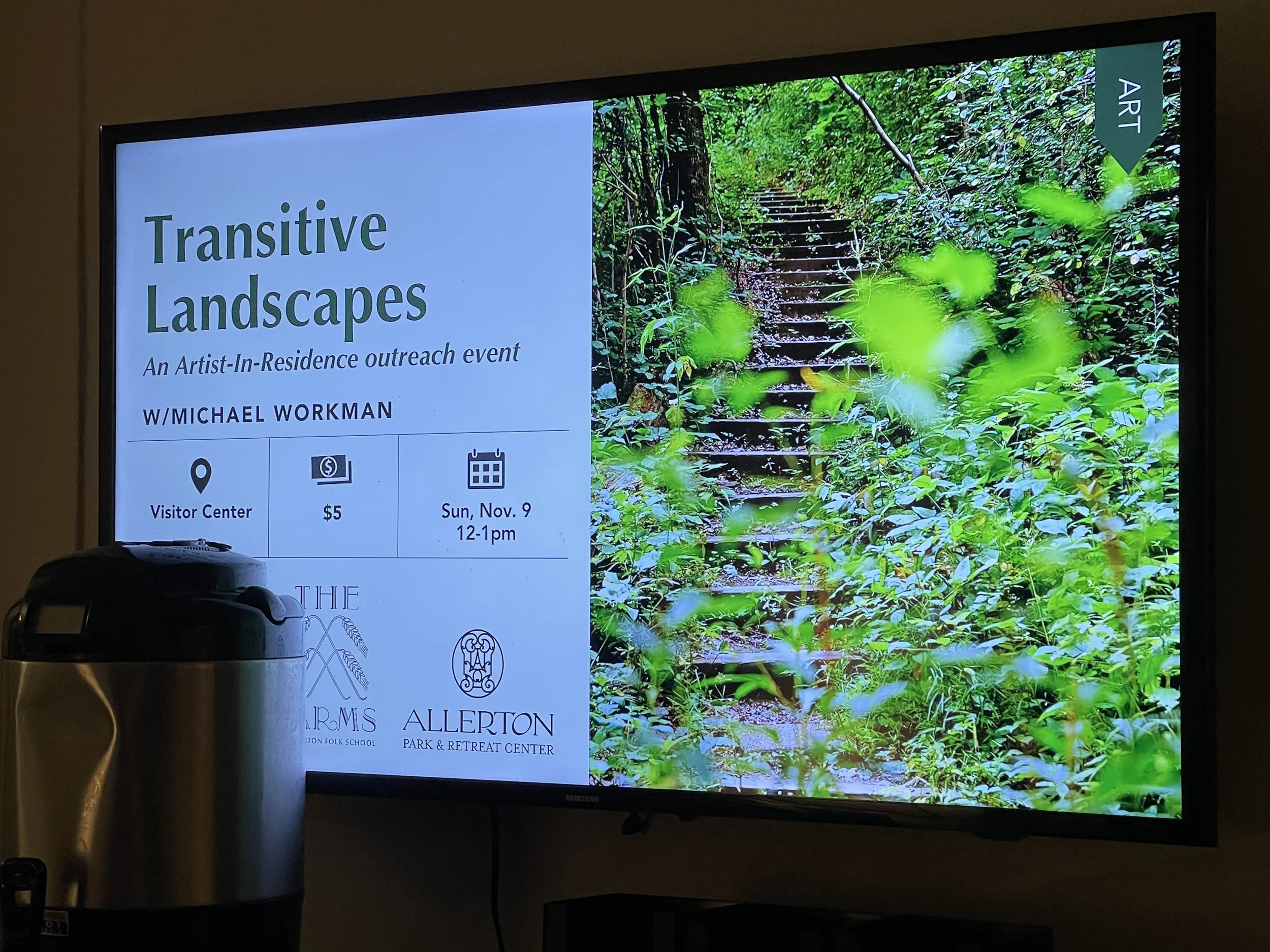

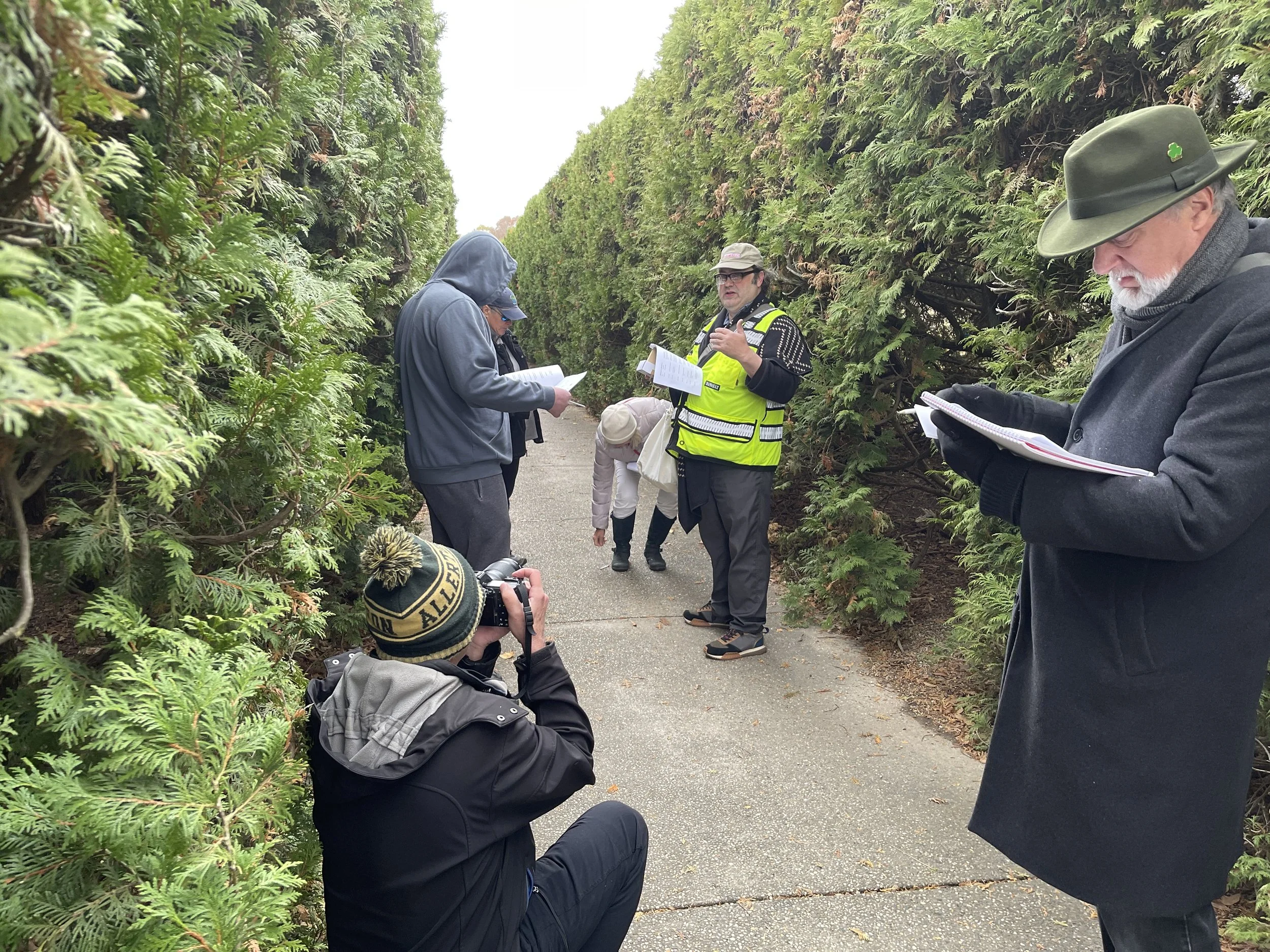

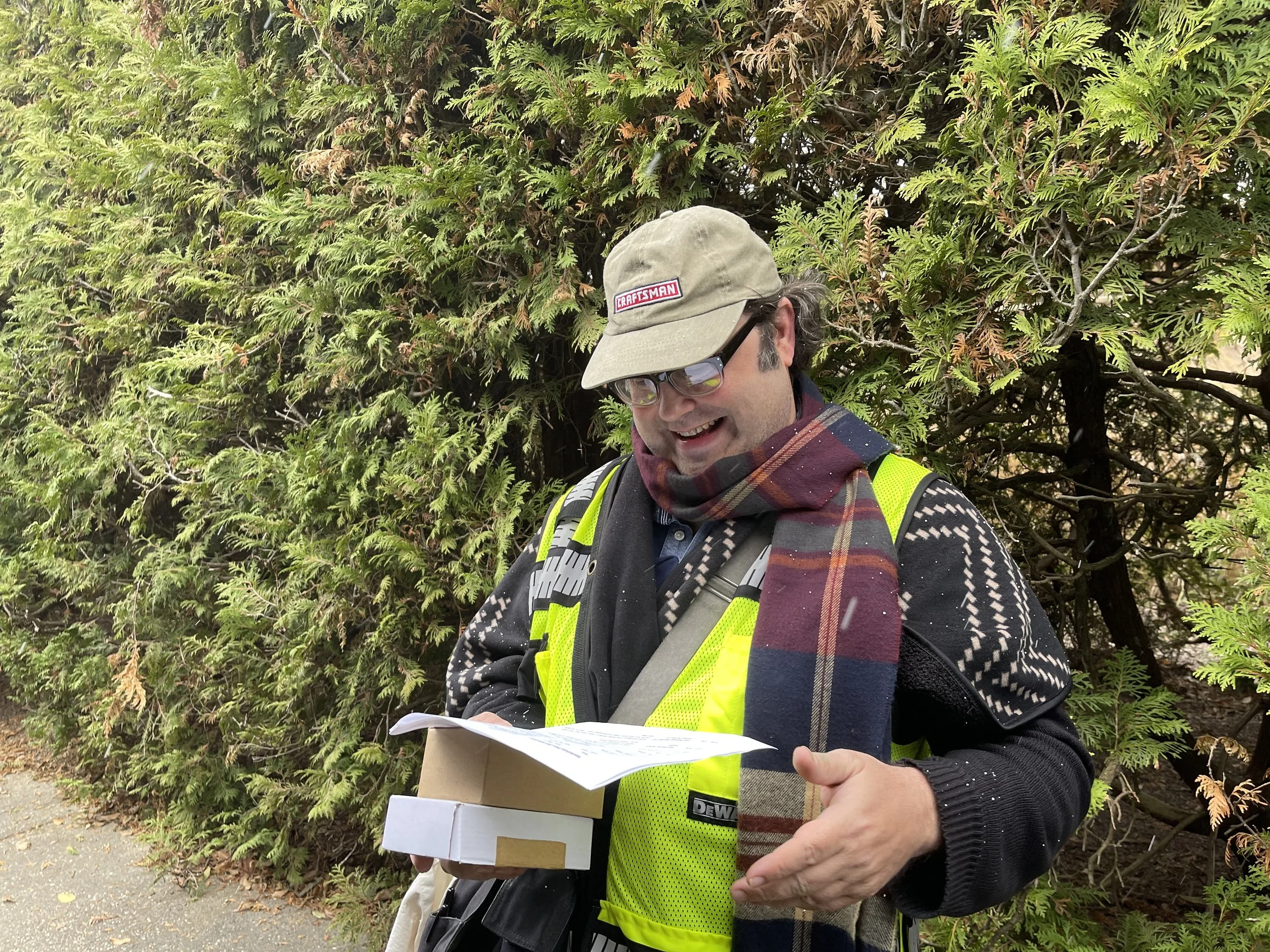

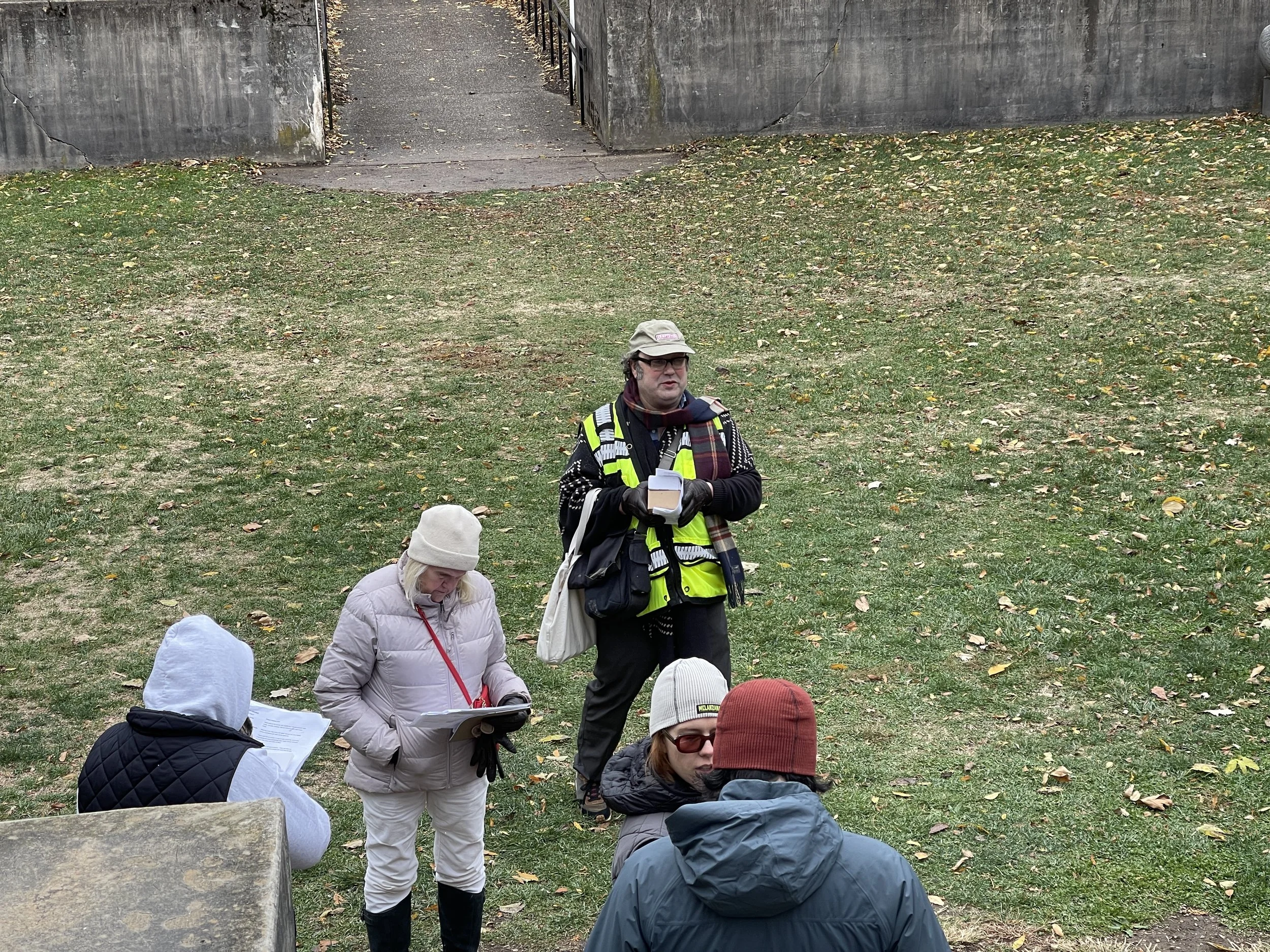

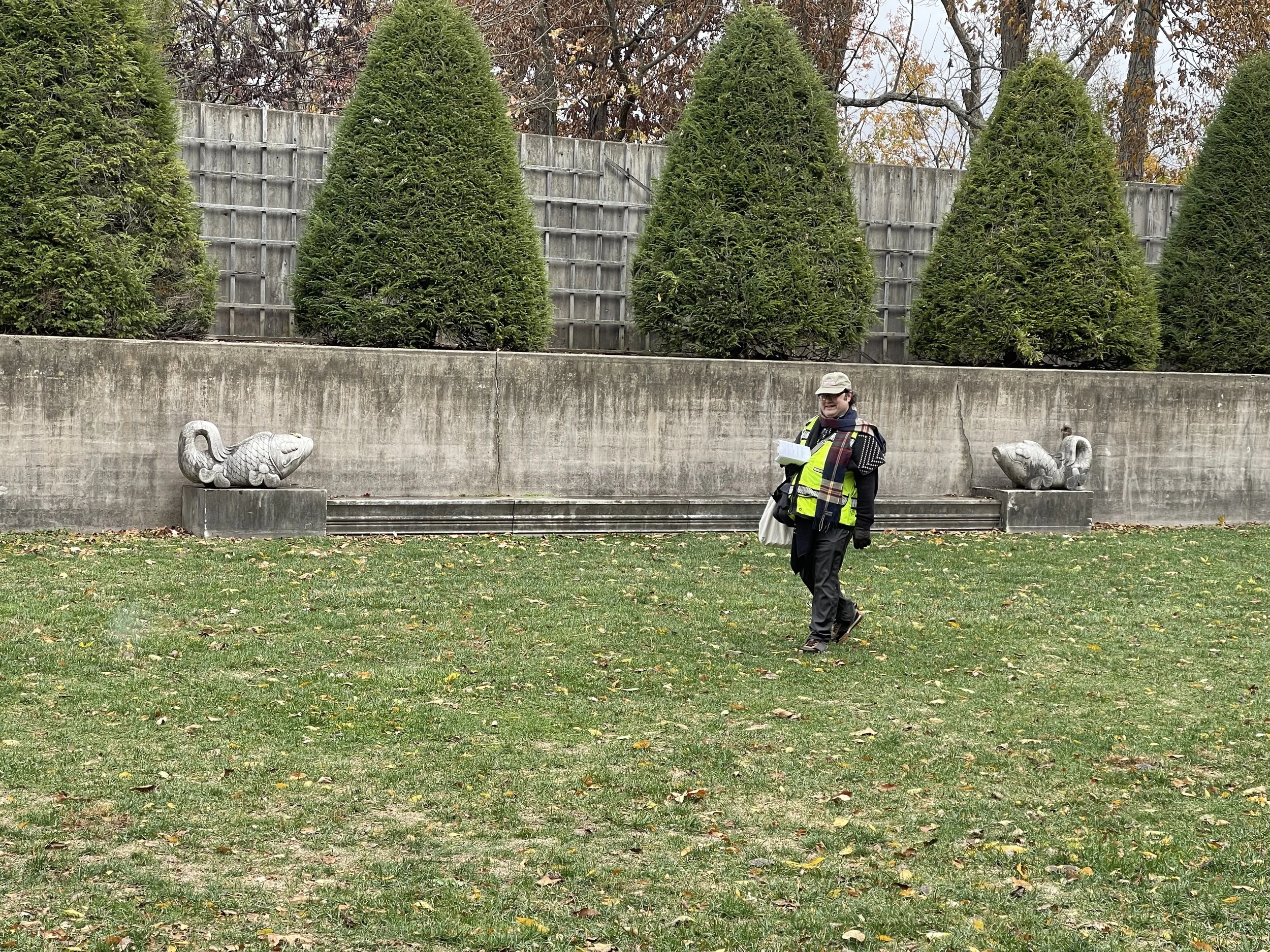

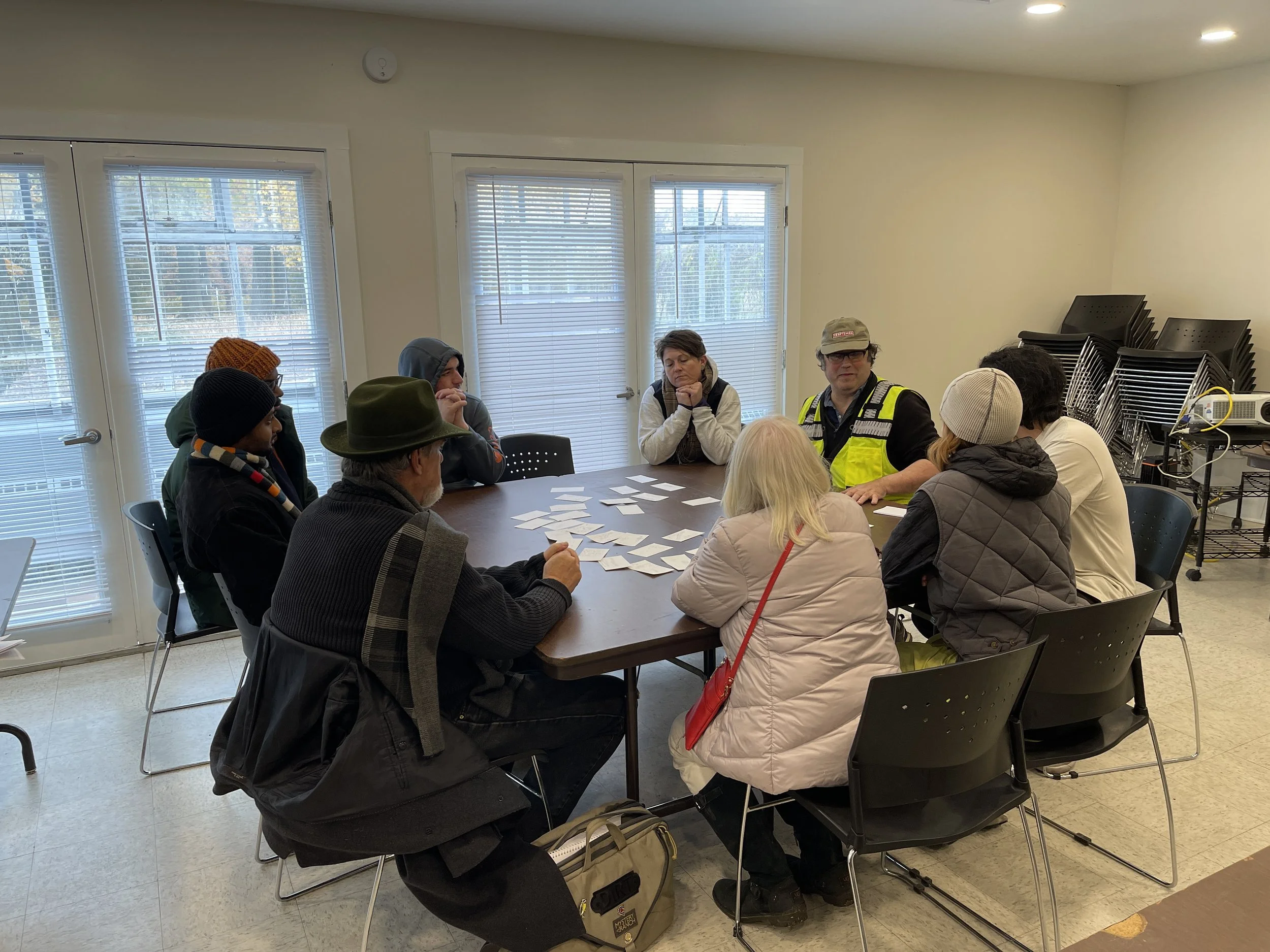

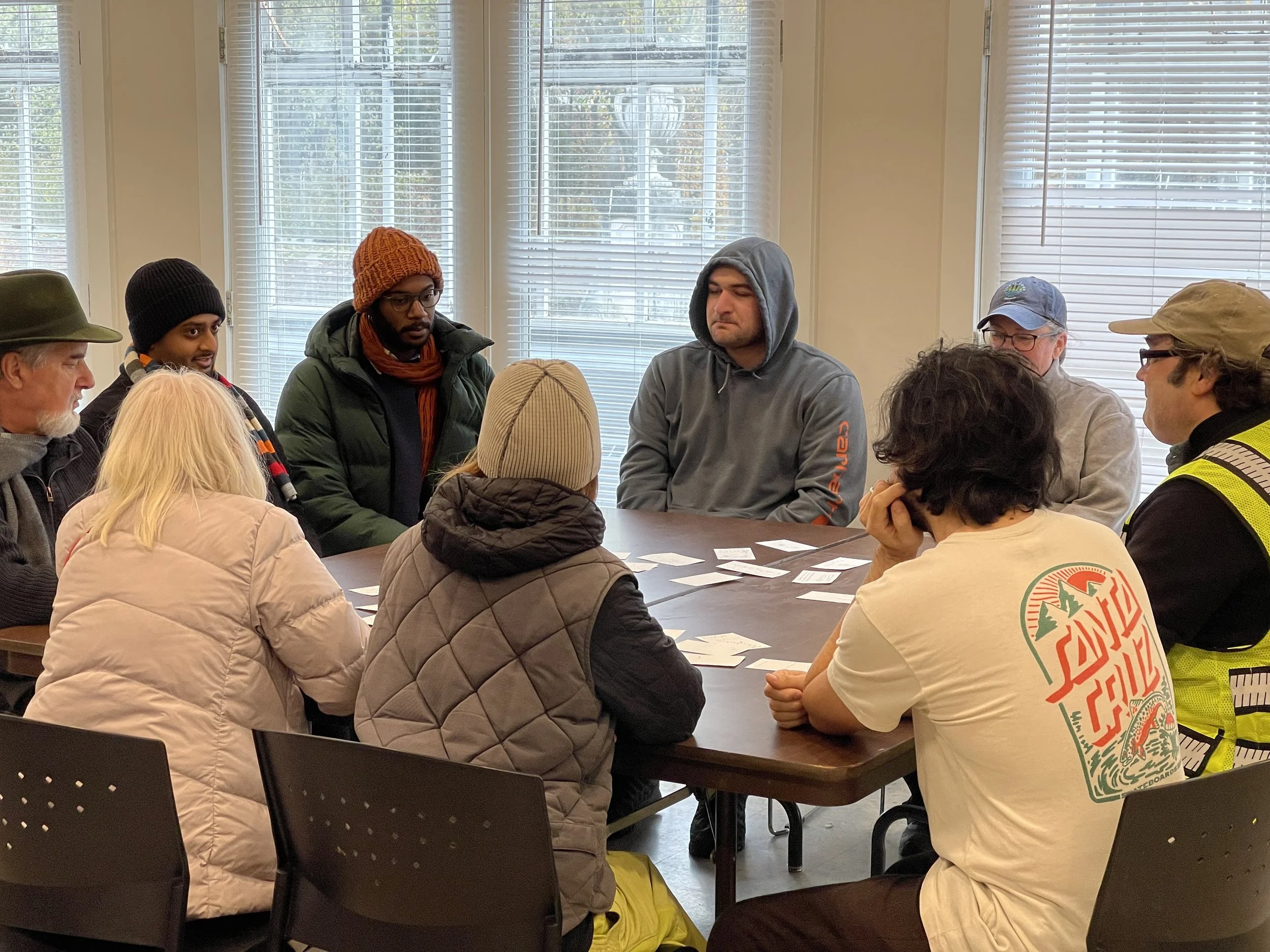

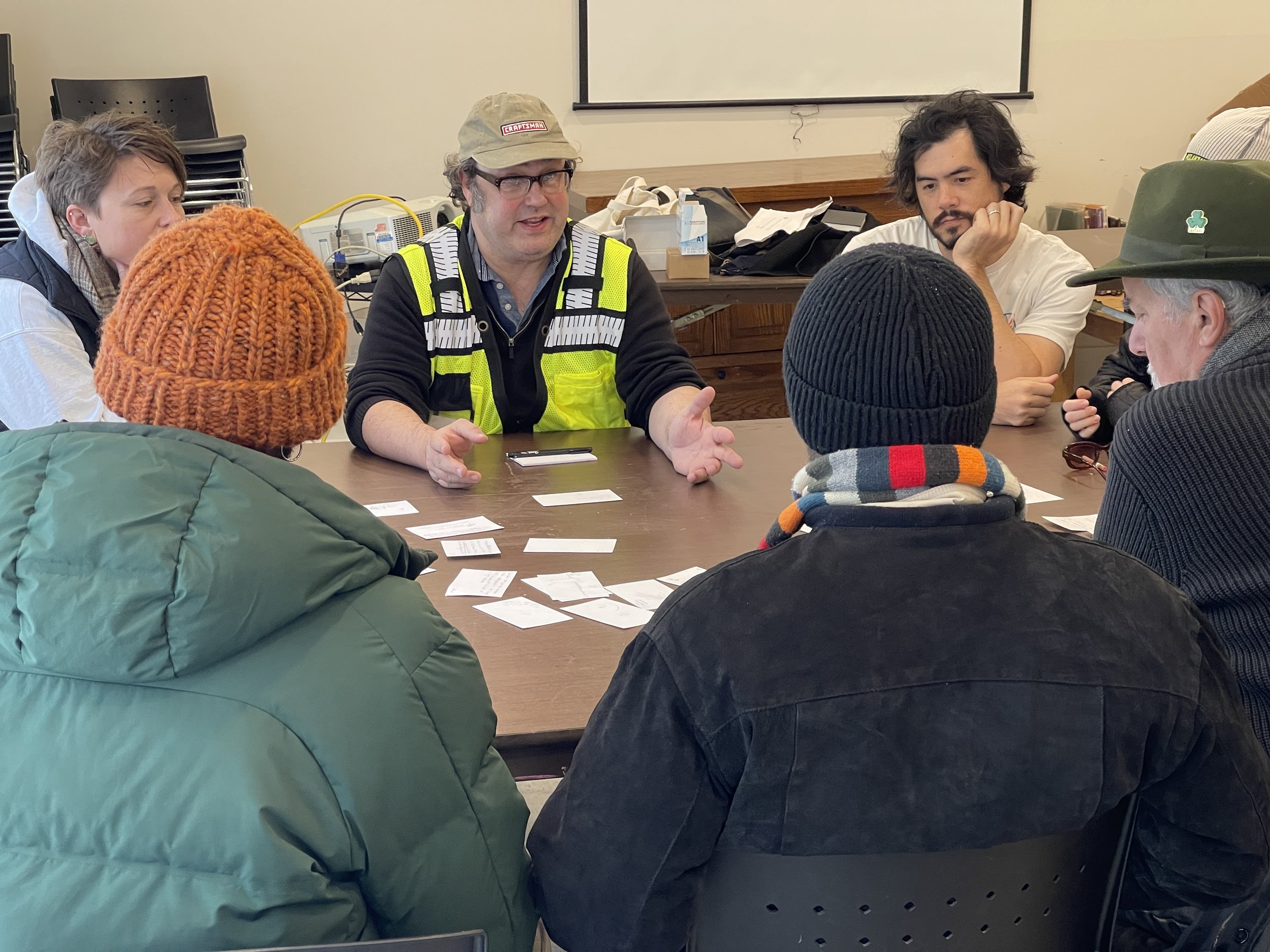

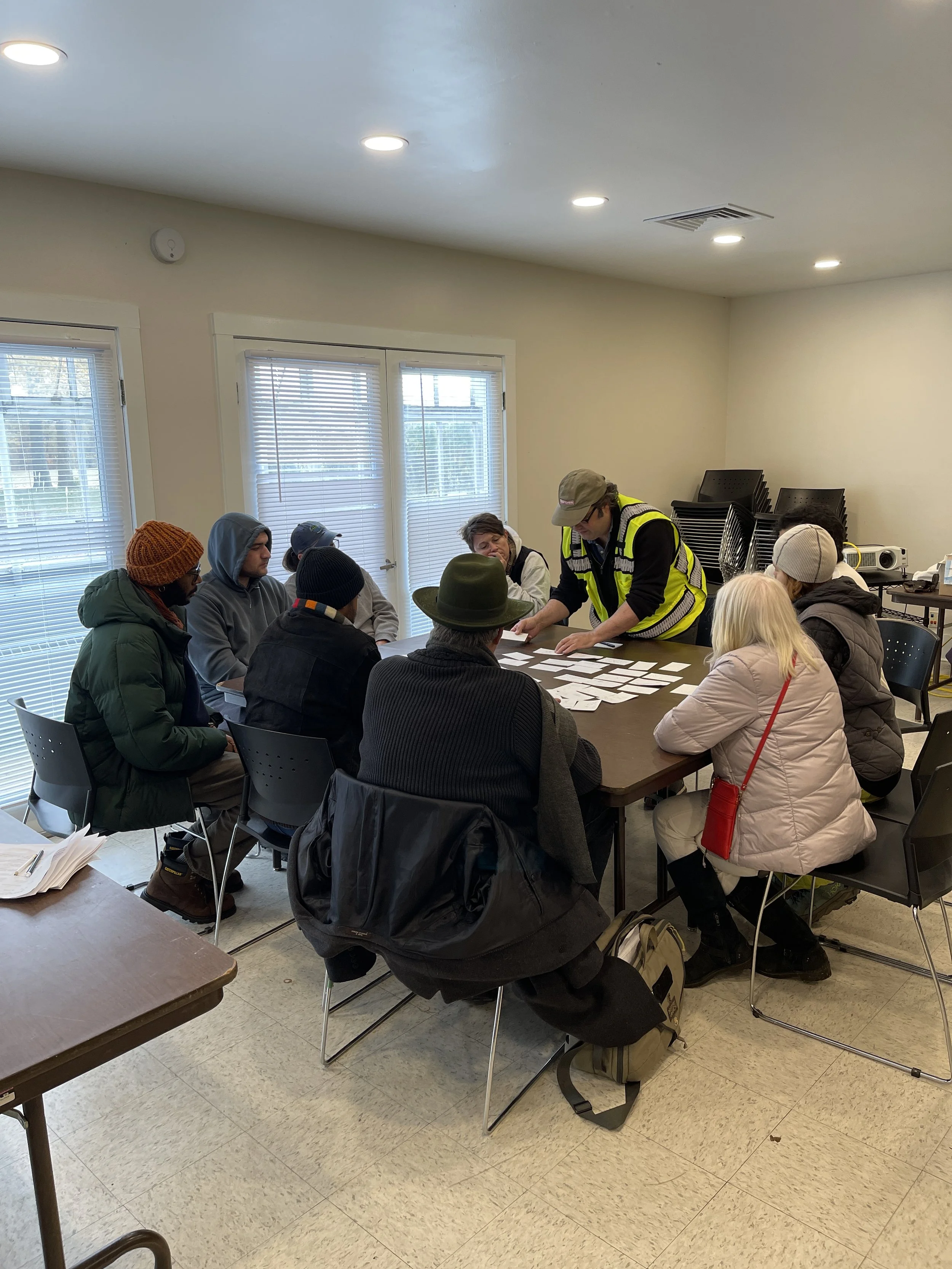

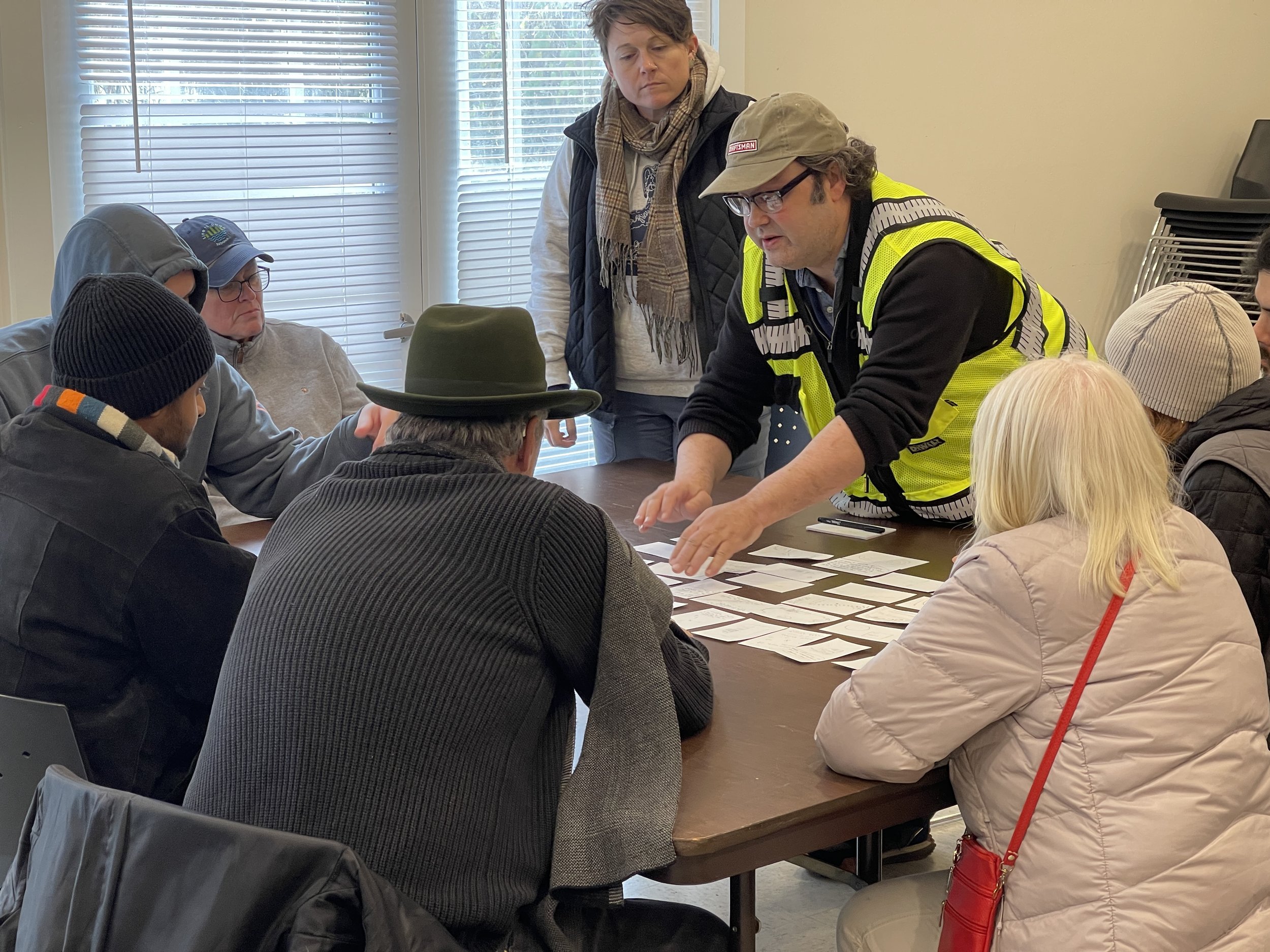

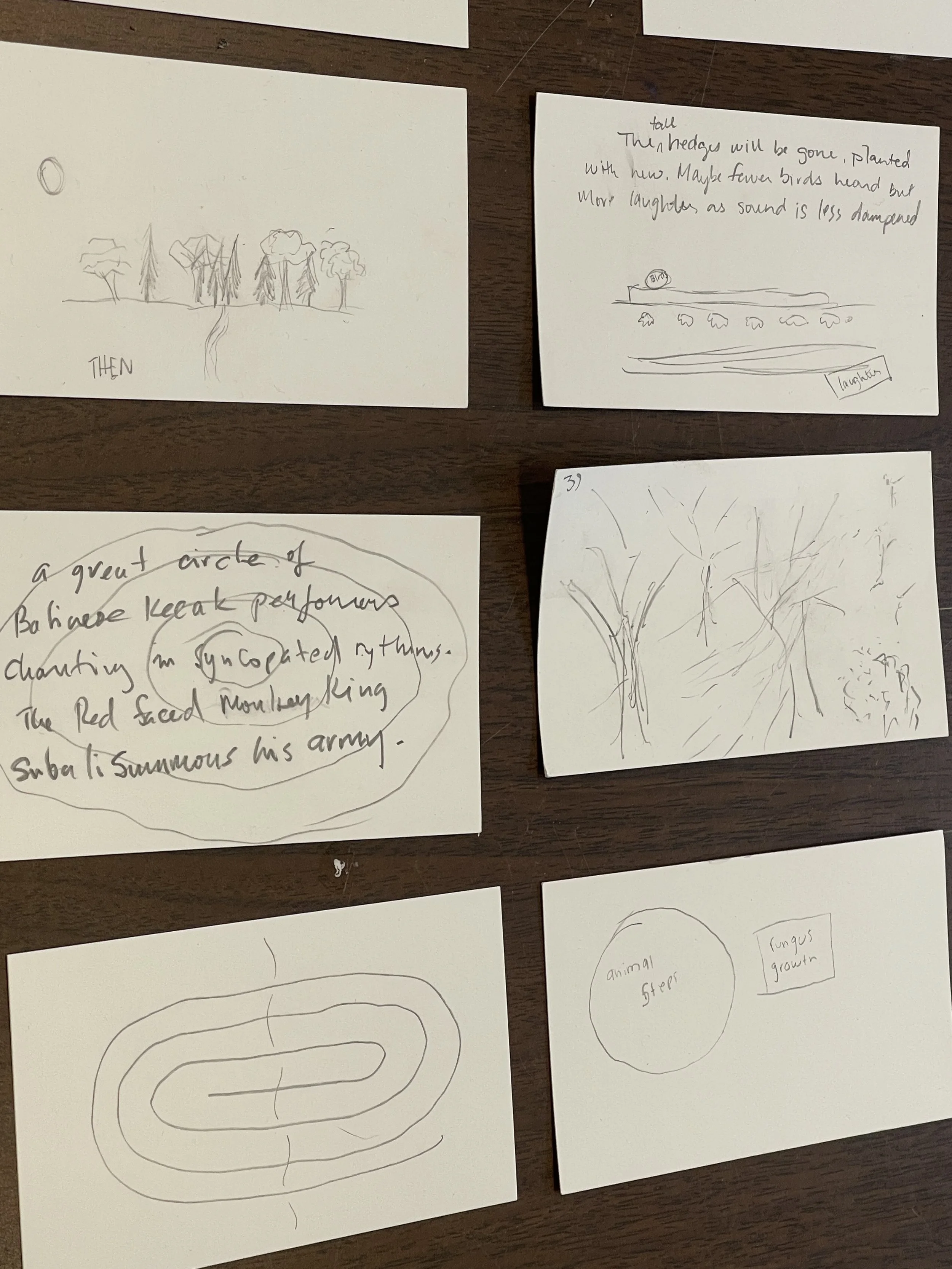

Then comes the big day for Transitive Landscapes. I’ve been thinking about what to do with this from the beginning, long before arriving at Allerton. The place presents this clear dichotomy between nature and art—most visitors see the sculptures and architecture as embellishments within a larger natural frame, a kind of curated wilderness. I want to push against that. But it turns out the nature I'm mapping is my own too, or rather—my own as part of an actively imagining community. Presented as part of "The Farms,” it fits into Allerton's year-round educational program of folk school workshops, though one a little different from the usual approaches. Rooted in conceptualism, absurdism, Dada, contemporary performance poetics and the allure of a shift in the human perceptual register; rather than to look together, it is meant to help activate the ability to perceive and record experiences of the imagined place. These are also, of course, legitimate experiences, just as reading a book is a legitimate lived experience. Even an imagined soup, described on the page, can elicit the re-cognitive brain activity as if its rich aromas were actually filling the room.

Thus, this workshop comes to be designed as a journey of perceptual discovery, guided by the effort to lens and articulate the unique perspectives of this imagined worldview, I encourage participants to search for themselves on the guided walk—the artist’s world drawn out of the studio and into the landscape. I write the text for it in the early days here and map it across the garden’s vast architecture—through its mazes, hedges, and hidden nooks. At each site, I peg a short performance prompt: invitations to reimagine the space two hundred years ago, or as inhabited by other, unseen creatures, or prompts to listen for sounds that might have existed here in prehistoric times. I'll post the workshop after the diaries are completed, which anyone can use to go on the walk themselves. It includes QR codes for those who would like to mix responding to the mapped prompts with audio researched to help provide resources for enriching place history, including recordings by previous Allerton Artists-in-Residence, recordings of residents maintained by the Monticello public library, and other audio.

Afterward, I sit for a long while in my chair in the studio, staring up at the ceiling, thinking about everything that has just unfolded. Sometimes that’s the only way to process it—just to be still, to let the experience settle without trying to fix it too soon in writing or image.

Now, as I prepare for the third and final week, I’m aware of how much has already changed: in the weather, in my body, in the way I’m seeing the space. The A-frame feels as if it has evolved more into a space of potential habitation, and the work feels like it’s beginning to find its form. What started as a period of acclimation has become an Active Investigation. The deer are still there at night, all around, still forging and gathering. The air smells sharper. The light is colder. And I’m beginning to understand how this place folds in time around me, keeps teaching me new ways to be still. Time, soon, to venture out to find the fabled centaur in the forest. -0-